Robert Louis Stevenson once explained that he travelled “not to get anywhere, but to go.’’ The great affair, he said, was

to “move.’’

“Sure,’’ I would have replied had I been there in the 19th-century novelist and travel writer’s study, listening closely, single malt in hand. “Movement is just fine. But for me, the whole thing is, well, more liquid. I sail, and get on planes, and pilot my car in quest of interesting drinks.’’

This is the point where Stevenson would have either refilled my glass, or sent me packing.

main image: rio de janerio, top right: iceland geizer, Bottom right: Brazil riVer cruiSe

But let me explain. It isn’t daylight I like, but dusk. And similar to a ship at sunset, reaching a new port lets me moor for at least a night, and taste (I should say sip) what it has in store. I find out more from the snap of a country’s signature liqueur than by visiting sights or taking guided tours.

France, of course, has its Kir (a blend of creme de cassis and white wine) and  England enjoys its Pimm’s Cup (a gin drink using quinine and herbs). But for a traveler, these are only two of the world’s top cocktail-hour pours.

England enjoys its Pimm’s Cup (a gin drink using quinine and herbs). But for a traveler, these are only two of the world’s top cocktail-hour pours.

In Iceland recently for the first time, I ran smack into a juggernaut in a bottle called Brenniven and known to locals as the “Black Death.’’ Similar to Aquavit in Scandinavia, Brenniven is a Schnapps that’s made from potatoes and jazzed up with the scent of caraway seeds.

Much like a looming volcano – like the Icelandic landscape itself – this national drink is a raw and mysterious thing.

The scary-looking jet-black Brenniven label depicts Iceland’s coastline, as if it were a tipple just for fishermen. In fact, while trying to get a glass of Black Death down, I learned that it is excellent for chasing away the taste of Hákarl, an Icelandic delicacy derived from rotting shark meat. (No one had any Hákarl handy.) And I didn’t die from drinking my shot. But my throat and stomach felt like molten lava and my brain like a just-extinguished blaze.

During a rain forest cruise on Brazil’s Reo Negro, I was handed my first Caipirinha, a concoction that tastes as fresh as jungle fruits or flowers (that’s the lime in there), but that coils inside you like a cobra waiting to strike. I  started asking deckhands and discovered that Caipirinha comes from “caipira,’’ meaning a person from the countryside. But after a second glass, the name of this national drink started to sound to me like samba.

started asking deckhands and discovered that Caipirinha comes from “caipira,’’ meaning a person from the countryside. But after a second glass, the name of this national drink started to sound to me like samba.

“Caipirinha, Caipirinha,’’ I sang out loud on the windswept deck. “Copacabana, Ipanema.’’ (This was the work of cacha-a, a local sugar-cane- based rum.) The cries of parrots overhead blended in, along with splashes of fish and fat tropical drops from a storm. For the first time, I understood why Brazilians seem never far from a guitar.

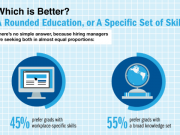

Sometimes a drink evokes what has been going on in a country’s work life. For reasons I have never understood, alcohol has an eerie sense of economics and often reflects the pace of the place where it is mixed and poured. An extreme example of this is in Myanmar (formerly Burma), which has been isolated for decades because of its repressive military regime.

Myanmar’s rural roads are clogged with herds of gentle cattle. Churning by on  bikes and donkey carts, everyone smiles. When my wife and I asked about spirits in a shop, the owner dredged up a dusty bottle about three-quarters full. Noticing our hesitation, he rummaged cheerfully in the back, and flashing a grin, presented us with a fifth of “Country Time’’ brand Burmese gin. We bought it on the spot.

bikes and donkey carts, everyone smiles. When my wife and I asked about spirits in a shop, the owner dredged up a dusty bottle about three-quarters full. Noticing our hesitation, he rummaged cheerfully in the back, and flashing a grin, presented us with a fifth of “Country Time’’ brand Burmese gin. We bought it on the spot.

An opposite universe, in many ways, was urban China. The busy Beijing restaurants I ate in pulsated with energy, with a zest for consumption that matched the frenetic streets. Unlike Myanmar, the carts here transported Peking duck, ready for slicing, and jingling bottles of baijiu, the country’s ubiquitous ‘white liquor’’ that is distilled from sorghum and can be as strong as 120 proof.

After a cup of the stuff was passed my way and I took a few sips, I began to feel that baijiu was more than just a drink. It was Beijing in a bottle. It reminded me of riding in Chinese buses, of touring around a car-choked downtown. “What is this taste?’’ I asked aloud, and a Chinese man at my table was quick to reply. “It tastes like diesel fuel!’’ he replied, clapping his hands and laughing delightedly beside four baijiu-drinking friends.

He was correct. I was slowly learning.

Time for another cup.

By: Peter Mandel – NICHE Magazine Winter 2013